On Gauge and the Mirage of Perfection

In knitting, as in life, perfection is an illusion.

It’s funny, really. We are awkwardly configured blobs of limb-studded flesh wrapped around articulated skeletons with hundreds of individual bones. Our bodies are shaped by our genetics, our choices, and our experiences (both voluntary and involuntary), and for many of us, this makes buying off-the-rack fashion a complex proposition.

I can’t buy a pair of jeans off the internet with any kind of reliable success. I have a deep curve at my lower back; a high, round butt; powerful thighs; calves so impressive that if I buy denim insufficient elastic, I can’t pull the legs up past my knees. I know my sizes, or at least what they’re supposed to be. I buy jeans made by brands that provide size charts, and I match them dimension-to-dimension to other pairs of jeans I already own and wear, and yet when I tear my new pants out of their mailers and attempt to yank them onto my body, nine times out of ten, it’s a no go.

We are miraculously complicated creatures, is what I’m saying. Our clothes are approximations, echoes of the shapes of us that we zip and button ourselves into, hoping they will feel the way we want them to, touch us and not touch us how we want them to, move with us how we want them to, and, most of all, look the way we want them to.

Sometimes they fulfill our expectations. Often, though, the clothes we buy are not quite what we thought they would be. They don’t fit, or they fit but not how we wanted, or they fit how we wanted but move wrong, or wear wrong, or feel wrong. We’re used to this. We expect it.

Let me say that again. We expect for there to be a gap between the dreams we have for new garments and those garments-in-reality. We expect to be forced to adjust — so much so that the adjustment usually happens without comment. We don’t get angry when a sweater we bought off a picture and a size chart on the internet turns out to be a little shorter than we imagined. We adjust. We learn to live with what it is instead of what we wanted it to be.

And yet, when we knit sweaters, we often expect them to turn out exactly as we hoped. If they don’t, we consider them failures.

We apply this binary even knowing that knitting a sweater is more complicated than cutting and sewing knit fabric into the shape of a sweater. A cut-and-sew sweater has multiple pieces and relatively firm seams. A hand-knit sweater that is made in one piece from the top down is a single seamless chain of looped string, which we anticipate — outrageously — will be able to be draped over a body without changing shape in any way.

We expect our knitting to behave. In fact, we expect it to behave in a way that nothing does behave. We expect it to behave in a way that defies physics and human experience and everything we collectively understand about art. And we hang the weight of these unrealistic expectations on gauge.

Specifically, we hang our unrealistic expectations on The Gauge Swatch.

Gauge Is Not Magic

Conventional knitting wisdom says that if we knit a four-inch-by-four-inch square in the same stitch pattern as the garment in our mind’s eye, using the same size needles we’ll use for our garment, and if we then wash and block that square in the same way we will wash and block our garment, and measure it carefully, we can discover exactly how many stitches and rows of knitting we need to make to produce the garment. With our correctly executed Magic Gauge Swatch in hand, we can sally forth to plan a sweater that will turn out the size we intend it to be, after which point we will swan around in it, smug and delighted with ourselves and our superior brains.

I mean. Guys. There’s a reason knitters say that swatches lie. When you make a gauge swatch, wash and block and measure, plot and plan, and then end up with a garment that is eight inches wider and six inches shorter than you intended it to be, the feeling of betrayal is intense.

But I swatched! I knew my gauge! The gauge swatch must have LIED.

It did not. There was a lie, but the lie was not emitted by your swatch. The lie was the premise of the Magic Gauge Swatch itself. The lie was in the unrealistic hope that a four-by-four square of fabric lying flat on a table could tell you everything you needed to know to make a sweater that would fit your three-dimensional, alive, moving, complex human body.

It’s such a bummer that it’s a lie. But it is. I’m sorry.

So. What, then?

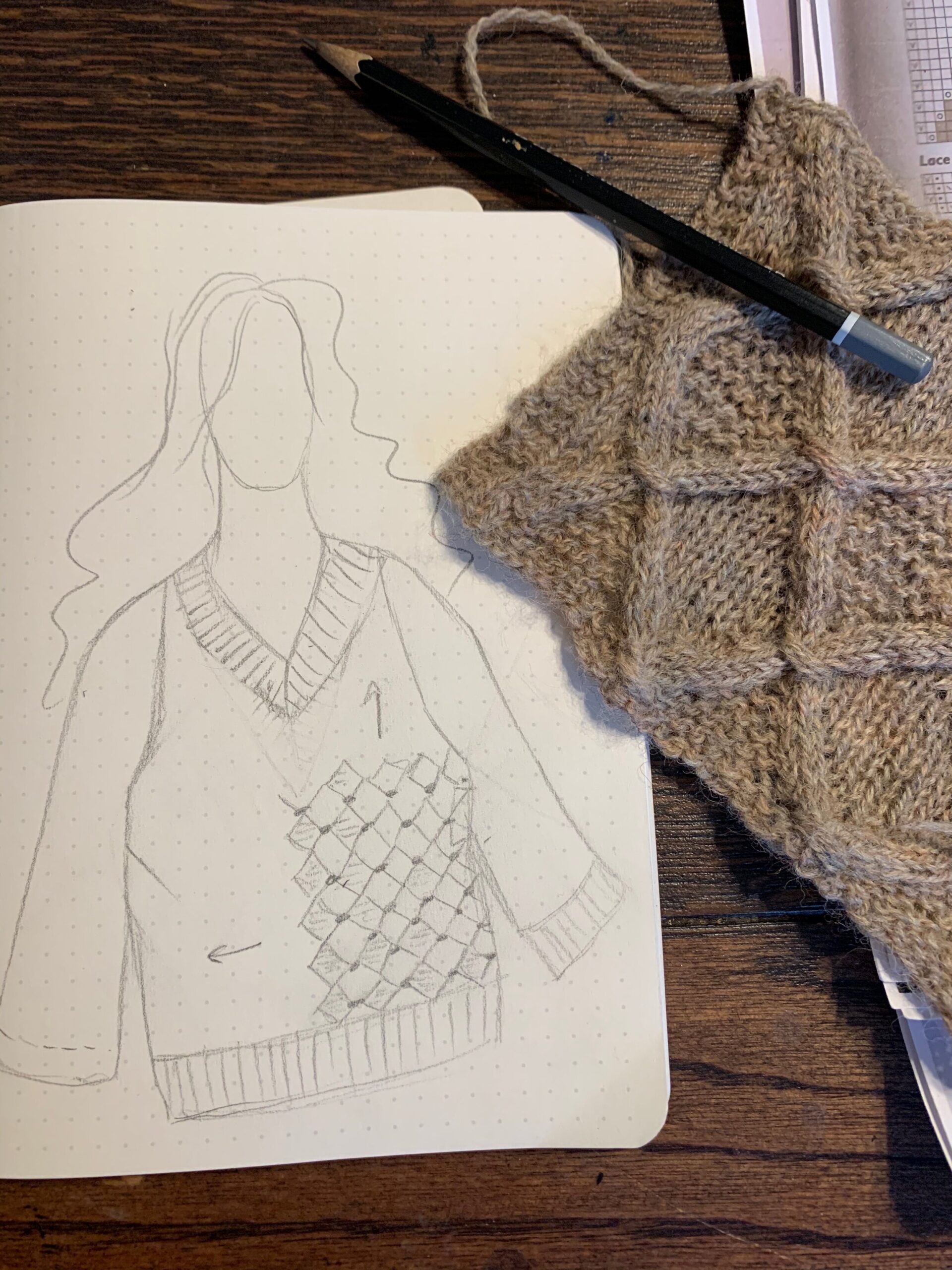

Obviously, we can’t give up on the notion of planning altogether. We do still want to make things that fit, and we want them to fit in particular ways, and we even want to be able to write down directions that will tell other people how to make things that fit them. I have a few thoughts on how to proceed, but first I want to resist what is so often the thing that comes after this question, the immediate next step my own brain wants to take, which is to propose a New Method.

Q: Well, if the four-by-four swatch isn’t enough, what DO I need to know to make a perfect sweater?

A. Oh, don’t worry. All you have to do is…

We shall sidestep that pit of vipers. It’s no good to replace one lie with another lie —and keep in mind, the lie that there is one way to achieve perfection is backed up by the lie that is the mirage of perfection itself. The lie is the idea that we can spend a week or a month or half a year poking around with sticks and string and then in the end not have to do the part where we adjust our expectations to reality.

The lie is the hope that if we work hard enough, if we try hard enough, if we plan hard enough, we’ll make something that is Actually Perfect.

I have been a maker for a long time, and I’ve known a lot of makers, and I’ve talked to quite a few makers, so I feel pretty confident in saying this: You will never make anything perfect. Even if it looks perfect at the moment you finish it. Even if seems perfect right at first. Even if you did every step of the making perfectly. Even if. You will never make anything perfect.

But. (There is always a but.) But, you will make things that turn out to be, if not perfect, then good. Good enough. Good in ways you hadn’t imagined. Good, not for you, but for the people you decide to give them to. Good, not for the body you had when you made them, but for the body you end up having five years in the future.

You will make things that are good because they satisfy you, good because you have such beautiful memories attached to them, good because they feed your soul, good because they kept your hands occupied when your mind was fretful and grieving, good because they remind you of someone or some place you never want to forget, good because the yarn was so gorgeous on the needles, good because you gave them to your kid, who gave them to her kid, who, long after you were gone, wore one of the things to made on an autumn afternoon at a park in a town you’ve never been to.

You will make good things. You will make so many good things, and they will bring you joy — if you can let go of the mirage of perfection.

Still, Planning Is Possible

So let’s say, for the sake of argument, that we have broken the spell, released ourselves from the mirage, and now we are ready to knit a sweater without the expectation of perfection.

I mean, we’re not ready. We are frail humans conditioned by decades of brainwashing by sexist, racist capitalism, and the best we can do most of the time is to recognize that we’re poisoned and write Progress, Not Perfection, Baby! and Smash the Racist Capitalist Patriarchy! on the whiteboards inside our brains.

Nonetheless, let’s pretend.

It seems pretty clear that we can’t throw out gauge altogether. At least, if we hope or intend to make something of a particular size, we still need a way to narrow down the possibilities of how many stitches to begin with, and knitting a gauge swatch gives us a starting point a lot more rapidly than, say, knitting an entire “test” sweater, washing it, measuring it, and then ripping it out and knitting it again to the right size, which no one would want to do, because it would be horribly boring. If we’re willing to commit an hour to making a four-inch-by-four-inch gauge swatch, washing, and measuring it, we’ll at least end up with some ballpark numbers to use in planning.

If we can stand to do it, we can even make that test swatch bigger — say, as big as one whole ball of yarn from the project — or we can take a card from Elizabeth Zimmerman’s deck and make a “test hat,” which gives us a chance to play with the yarn and the stitch pattern, and which will most likely fit someone even if it doesn’t fit us, and which produces something a lot more useful than a swatch.

We might not be able to stand it, though. I’ve made boatloads of swatches, but very few wider than four inches (sometimes they’re longer), and exactly zero test hats, despite thinking it’s a clever idea.

And anyway, no matter how much or how well we swatch, at some point we’re going to have to get comfortable inhabiting reality. The reality is, there’s only so much a swatch can tell us. This means we’re going to have to check in on our garment while we’re making it. If we’re knitting it in pieces, it probably means blocking and measuring those pieces after each one is finished to see if the size is working out. If we’re knitting our whole sweater in one piece, it means stopping to try it on and check how it’s fitting.

“Inhabiting reality” also means making some educated guesses about how our knitted fabric will behave after it’s all finished. Will it get bigger? How much bigger? Is it going to be heavy, and is the weight of it going to pull in any particular direction? Is the stitch pattern going to pull in even more when I’ve knit a whole big piece out of it? Does this kind of yarn have a habit of shrinking or growing in a notable way? (Silk and linen, I am side-eyeing you.)

I once read a knitwear design book that recommended pinning your swatch to a cork board for a few weeks to see how it behaves. It’s been thirteen or fourteen years since I read that, and I still haven’t done it, which suggests it isn’t a tip I’m going to adopt in my knitting practice. And that’s part of inhabiting reality, too — paying attention to what you are willing to do, how much you care about the exact fit of your finished object, and how much work you’re interested in taking on to get as close as you can to the size you want.

The truth is, you can knit and block an entire test sweater and wear it around awhile before ripping it out and re-knitting it to the size you truly want. It would be a tiny bit weird to do that, but no one is stopping you. Plenty of people knit the same sweater more than once, adjusting the fit of the second to make up for the deficiencies of the first. Plenty of people also use a favorite yarn over and over again, and the more they use it, the more information they have about how it behaves. Maybe doing that kind of thing would cramp your style, but you have no problem with taking your top-down sweater off the needles to block it when you get to the armholes so you can try it on and see if you’re good to go or if the fit is so far off the mark that you need to start over.

Which brings me to a question that connects to one of the more painful dimensions of inhabiting reality: How willing are you to rip your work out and try again? If you’re dedicated to the proposition of making sweaters that fit the way you want them to, and if you don’t have an unlimited yarn budget, it’s hard to get around it. Sometimes you have to go backward to make forward progress.

Say It with Me: “Process is My Jam”

I’m such a fan of forward momentum. Aren’t we all? But the longer I hang around the earth, and the older my kids get, and the more stuff I make — novels and sweaters, dinners and Instagram posts, couch pillows and backyard videos for the church pageant — the more I’m trying to embrace process.

Process is where it’s at, if you’re trying to make a sweater that fits. Process is everything.